Jacob Baytelman

Building software since 1998

Innovations of Tomorrow Projects Contact meSafety and security

The best fight is the one

you managed to avoid

you managed to avoid

These days I have a pleasure and honour to be working on a project for safety in crowded places but my personal story of making safety precautions an integral part of my life started about 30 years ago, shortly after the accident at Chernobyl nuclear power plant. My native city accepted refugees from Chernobyl area, some of them became my new classmates and told me in detail all they had seen.

For the first time in my life I learned about emergency response to a disaster or catastrophe: what the authorities and ordinary people had done vs what the news were reporting vs what instructions stated. By the way, a great number of training alerts through all the country followed that terrible accident, my parents were given gas masks at their offices, instructions for the population were distributed to our post boxes and regularly broadcasted on TV. I remember, some of them required the tenants of our house to arrange a kind of a bunker in the basement. Of course, nobody actually bothered, but as a child I could not understand that "stupid negligence".

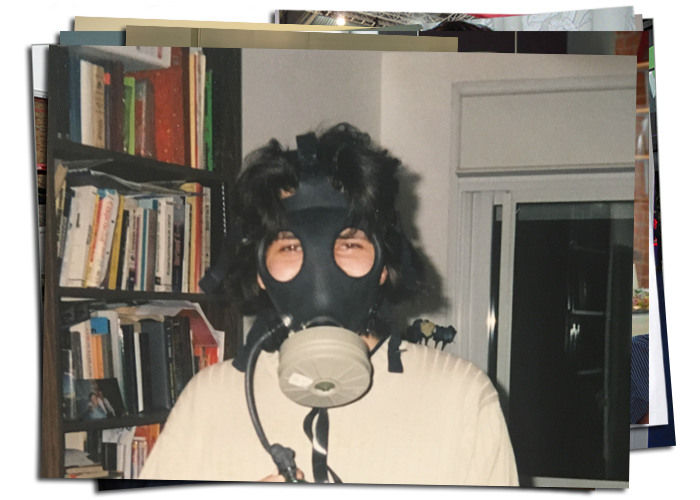

Many years had passed since then, I moved to Israel. In the beginning of the new millennium my son was born and I received gas masks for all the family including a special model for the baby. Instructions for population were provided too. Some time later the country faced a threat of rocket attacks, corresponding instructions followed. Unfortunately we had some chances to practice those instructions in the real life, so we do know the drill now quite well.

In more peaceful days we got used to regular inspections of our bags and car boots each time we enter a shopping mall or a train station or any other public place. I am explaining all that just to give you a perspective of my entire life "on alert". Constantly. Everywhere.

As soon as I enter a new place I find myself examining the territory almost subconsciously: my eyes are scanning for suspicious objects or people, unattended bags, emergency exits, etc. Being always a bit "on alert" has become my normal lifestyle. Just a little bit more than necessary. It is simple and easy, but it can save lives.

Once I went to a supermarket in Ukraine to grab quickly 2 or 3 items on my list. All of a sudden I heard a fire siren, then a voice warning demanded to leave the building immediately. Surprisingly, many people simply neglected it and continued shopping. All those queuing at the cash desks did not even think to move. People with children were absolutely calm and paid no attention to the warning. I came up to a guy with a little girl and told him to go out. He asked whether I was serious. I did the same with three or four other families with children. They all asked me if I indeed thought it was necessary.

Hey guys, what else do you expect when you hear a fire warning? Do you want to see flames and smoke to realize the danger?

Then I approached a security guy at the entrance and suggested to stop letting people in. He asked me why. The warning was to leave the building, not to stop entering it! It might have been a funny story about a software developer who literally executes his wife's instructions. But it is not, because it is about the life and death. I could not know whether it was a big fire or whether it was a minor accident or even a failure in the alarm system. But for the sake of your own safety and safety of your children, would you really want to stay and check it personally? Those people seemed to do.

We deal with complex systems every day. The truth is that many objects around us are such complex systems: our cars, public transportation, shopping malls, etc. Any complex system has a sort of multi-segment chain of foolproof protection. That is how they are built. For example: in your car there are 2 mechanisms for keeping it stationary: the low gear and the hand brake. Your car will be completely motionless if you park it even on a slope and either leave the stick in the low gear (or the automatic transmission in the "parking" position) or engage the hand brake (assuming it is in order). Most of us do both, just to be on the safe side. But some go even further and turn the steering wheel in the direction of the sidewalk, so even if the first 2 options fail (very unlikely though) and the car starts moving, it will stop as soon as the front wheel touches the curb. Exceptional safety freaks can take it to the extreme and put a stone under the wheels.

This example explains how a failure of one segment of a chain in a complex system can be compensated by normal functionality of other segments. Disasters happen when more that one segment fail.

A fire in the trade center in Kemerovo (Russia) caused many deaths. 2 segments of the fire protection system failed there: the doors of the cinema on the upper floor were blocked and people could not get out, that was the first segment. The alarm system did not work (or was turned off because somebody thought a false alert had caused the annoying noise), that was the second failed segment. If any of these two functioned correctly, the tragedy might have been avoidable. The alarm could be heard and thus people outside would have come to rescue the blocked; or no one would have been blocked at all.

Very often our own negligence is such a failed segment. In other words, our over-precautious behaviour could create an extra segment as a supplement to any system. In 99.9% of cases it is as useless as airbags in your car, but in an extremely rare 0.1% it can save your life. The problem is that you cannot know in advance when and where you get into that rare 0.1%.

To be continued.

| J.Baytelman | April, 2018 |